Last week I attended the Lavender Languages conference for the first time, and it was my best conference experience yet! There were plenty of interesting talks on nonbinary topics, and I of course talked about nonbinary pronouns again. This time the focus was on the nonbinary participants’ personal experiences, but I also compared the nonbinary and cisgender participants’ attitudes towards nonbinary pronouns. Here are my presentation slides.

I have already written about some of these aspects earlier on this blog ( with my previous presentation on the thematical analysis and attitudes, my ISLE presentation on nonbinary pronouns, and my very first poster), but in this post I will extend on the nonbinary participants’ personal experiences with pronouns.

First, I took a closer look at the reasons the nonbinary participants had for accepting multiple pronouns (slide 6). The two main reasons seemed to concern practical reasons and the type of relationship the participant had with the person referring to them.

Quite a few of the nonbinary participants were saying that they would like people to use nonbinary pronouns to refer to them, but they did not feel like it was a reasonable or practical request; some participants said that they accept binary pronoun references because of that, while others wished to use a neopronoun, but ‘settled’ for nonbinary they, which was perceived as an easier alternative.

“I currently ask people to use ‘they’. I wish I could realistically ask for ‘xe’.”

“In an ideal world, I would ask people to use neutral terms, ‘they/ze’, however I do not do this yet because of practical reasons”

Some participants also talked about how it would not be reasonable to expect strangers to know what their pronouns are, and as such strangers could use different pronouns than friends or family. Others said that even people that know them might use different pronouns to refer to them, depending on what they are used to. For example, one’s parents might continue to use the pronoun assigned at birth, while friends might use they.

“It depends on the situation. I don’t have a single ‘correct’ pronoun that I ask people to use. In situations where people know me, however they know me by is fine. In situations where people don’t know me (a cashier, for instance), I notice and appreciate ‘they,’ but given it’s a one-time interaction, I don’t make a point of asking or correcting.”

“Either they/them, or the pronouns that go with the way I am presenting that day. However, this is more complicated in real life, because depending on how long I’ve known someone or what our history is, I may prefer that they only use he or only use she — for example, I don’t want to deal with my mom trying to use any pronouns but ‘she’, as she has always called me, and I want my chosen brother to call me ‘he’ because our relationship is that we are brothers.”

One of the nonbinary participants also said that while they prefer to be referred to as they, he would also be acceptable since at least it places them further away from their assigned gender; perhaps for this participant there are different levels to misgendering, being perceived as the assigned gender being the worst. Overall, the responses highlighted that the pronoun situation can be quite complex for nonbinary individuals.

I also talked about the importance of correct pronouns, which was one of the direct questions in my survey, and nearly 70% of the nonbinary participants felt that it is important that others use their correct pronouns (slide 7). However, again, context seems to matter. As mentioned, quite many of the participants acknowledged that people who do not know what their gender or pronouns are can’t reasonably be expected to get the pronouns right. In general, the participants also seemed quite understanding of people making mistakes with their pronouns even after they’ve been told what pronouns to use.

Another very important aspect that was brought up was concern for safety. By revealing your pronouns to others, you inevitably also disclose information about your gender identity. Unfortunately nonbinary individuals often still need to explain their identity to others, and in some cases this might lead to conflict or even put you in an unsafe position. For example, one participant said they need to always be prepared to terminate the relationship after the pronoun talk, in case things don’t go well.

“Yes and no. If it’s someone close to me I tell them which ones I prefer, and expect them to use those. If it’s not anyone too close I often just go with whatever they use, because I don’t feel like it’s worth it to explain my gender identity to them if they happen to lack understanding.”

“[It’s important], unless I am in the company of people who may cause me harm if I were to give my correct pronouns.”

I also asked the participants how it feels when someone uses the wrong pronouns to refer to them (slide 8), and 80% reported negative feelings, mostly expressions of hurt and invalidation, ranging from feeling invisible to non-existent, irritated to upset, sad to resentful, and the most common description was simply that it hurts. The participants also talked about how it makes them feel dysphoric, anxious about how they are perceived.

The participants also shared their experiences with language based discrimination (slide 9). About 80% reported having felt discriminated by language use, however not necessarily just by pronoun use (the question was more general). Again, the descriptions circled around feelings of exclusion and invalidation. In particular the participants talked about feeling excluded from references like ladies and gentlemen, men and women, and also he or she.

“(…) people like me are commonly left out of conversation and the validation of our identities is often dismissed as us being whiny.”

“ (…) Using ‘he or she’ in a generic way sometimes makes me feel left out, occasionally even a little less human, although I know it wasn’t the speaker’s intent.”

“[Using he or she] is deliberately leaving me and people like me out. It’s telling me that I don’t exist. It’s saying that people who were lucky enough to be male are female matter and I don’t.”

“Yes–people very often use language that is heterosexist and cissexist, and it’s consistently made me feel unsafe. More inclusive language choices are very important to me because of that.”

Some participants also brought up mocking neopronouns, which seems to be unfortunately common online. This was experienced as invalidating nonbinary identities, as pronouns have become to be so tightly linked to identity.

“I’ve heard several people actively mock neo-pronouns to my face, which feels invalidating and sometimes intimidating as a non-binary person even if I don’t use neo-pronouns myself. It indicated that they don’t respect my identity. (…)”

Refusing to use nonbinary pronouns was also felt as discriminatory, a few participants having had friends or family members who refused to use their pronouns.

“The refusal by many to accept the existence of non-binary identities that manifests itself as either an aversion to more recent pronoun constructions à la xe/ze or the use of the singular they does cause me a certain amount of distress. I sometimes feel like there’s a part of myself that I’m not allowed to openly express.”

“Yes! Some people have made a point to continue using male pronouns and terms for me *because* they know I’m trans, and are not okay with it.”

“Yes- most notably someone greeted me as Miss. Also, my dad refused to use my pronouns.”

Clearly, as these responses show, pronouns are much more than simple reference tools. Pronouns are tightly linked to gender identity, and as such, issues relating to one’s pronouns extend to one’s identity as well. Respecting someone’s pronouns entails the act of validating and acknowledging the person’s identity, while refusing to use the correct pronouns means rejecting the validity of that identity.

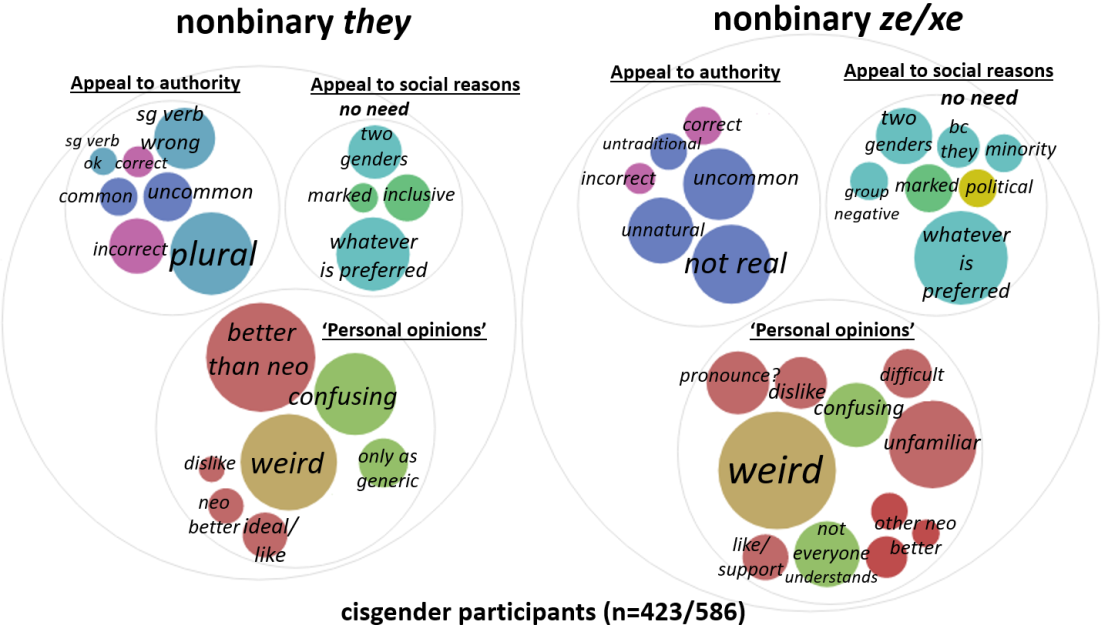

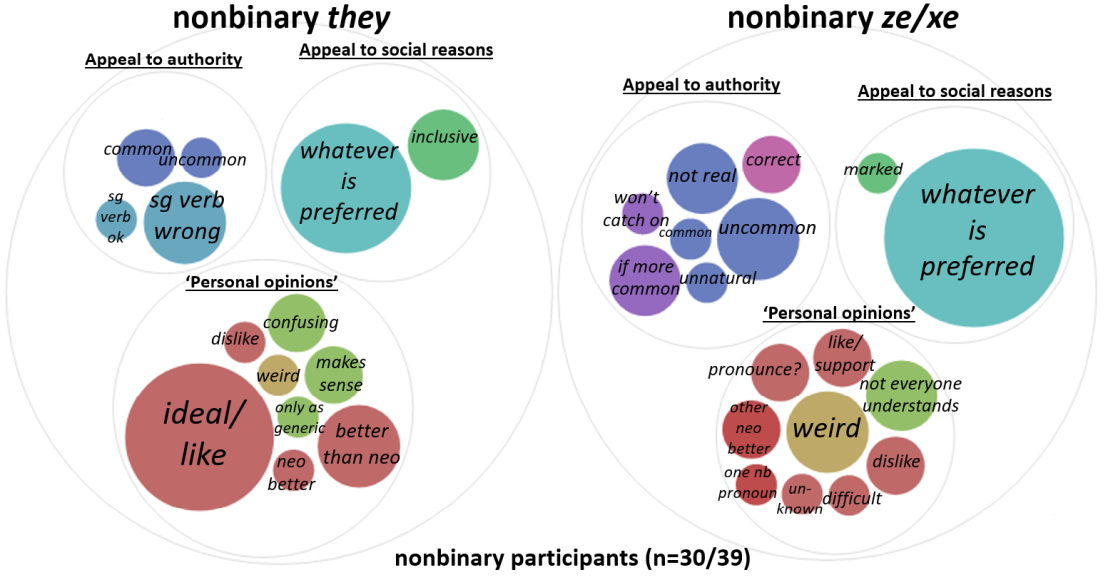

Finally, I also looked at attitudes towards nonbinary pronouns, again, but this time separating cisgender and nonbinary participants (slides 12 and 13). This time I presented bubble charts instead of tree maps, which I found to be visually more appealing but more importantly also allowing for showing the hierarchies and thematic groups. The bubbles are scaled for frequency, the different colors grouping together themes, and the inner three circles representing the three main themes I created, for each pronoun.

I have unpacked the results from the thematic analysis quite extensively in a previous post, so I will not go through the results in detail here. Quite importantly though, as the subsample of nonbinary participants is small (30/39 reacted to nonbinary pronouns), the smallest bubbles here represent only one participant, and the rest of the smaller bubbles mostly 2-3 participants. Taking this into account, there were really only two common themes among the nonbinary participants’ responses: the preference for they over neopronouns, but also indicating that everyone has the right to choose their own pronouns (whatever is preferred).

While many of the same themes that were coded for the cisgender responses were found among the nonbinary responses as well (although in low frequency), lacking completely from the nonbinary participants’ responses are indications that nonbinary pronouns would be incorrect, or that neopronouns would be confusing. The cisgender participants on the other hand did find nonbinary pronouns to be generally weird, uncommon, unnatural, and the neopronouns were often not recognized as real words (if recognized at all). Viewing they as the better alternative was a common theme among both cisgender and nonbinary participants. Overall, what can be concluded from these charts is that the nonbinary participants had generally more positive attitudes towards the pronouns than the cisgender participants.